For much of my working life, Japan was the place where nothing much happened in financial markets, where interest rates were stuck at zero, and stayed there for decades.

That has certainly changed in the past few years, and this last week has been anything but boring. It’s also been fascinating watching how headlines have evolved last week.

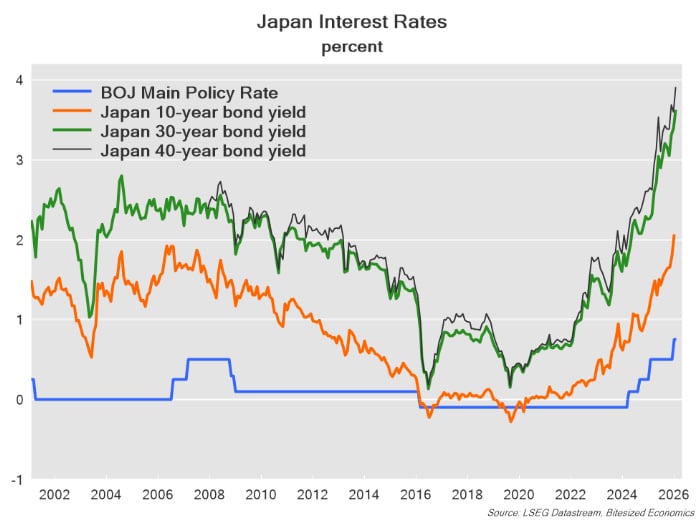

Firstly, there was the announcement by Prime Minister Taikachi to suspend the consumption tax for food for two years, and to call a snap election for February 8. We then saw Japanese bond yields spike. The yield on 30-year Japanese Government bonds (JGBs) spike up to 3.89%, and the 40-year year bond yield hit 4%, both their highest since issuance of these tenures began. The over 20 basis-point one-day move was somewhat troubling, and parallels were drawn to when Liz Truss delivered a mini-budget in 2022.

It then came out in a Bloomberg article by the lovely Ruth Carson that Japan’s yield spike was triggered by just $280 million of trading. Which for the bond market, could just be just one regular sized trade.

So, let’s just unpack what is going on here – is Japan’s government debt really in trouble? And if so, what should we make of it all?

In answering the first question, I’ll repeat what I mentioned in a piece I wrote in May last year.

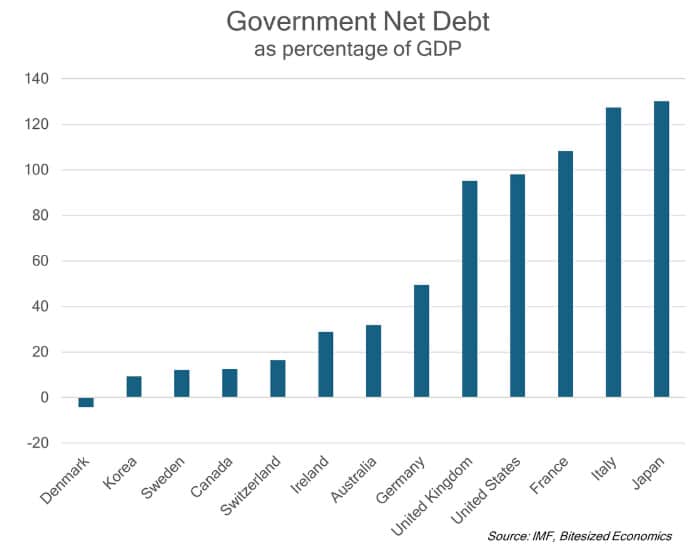

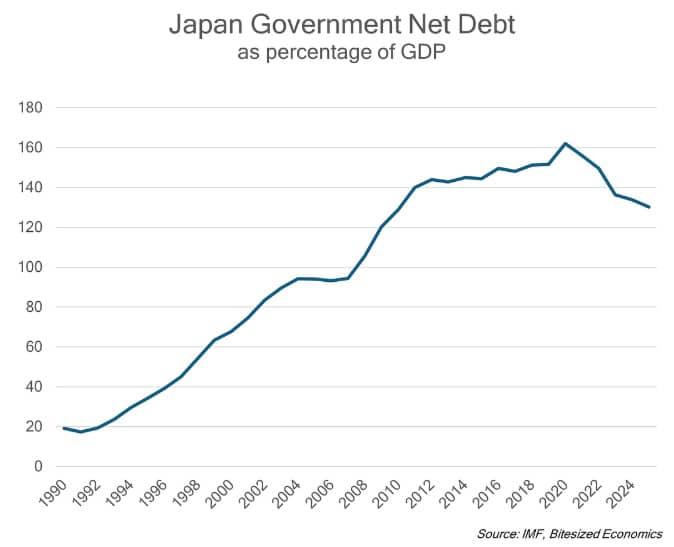

Japan’s government finances aren’t in the best position – net debt stood at a relatively high 134% of GDP in 2025 (gross debt is higher at over 230%), and Japan’s budget remains in deficit.

But it isn’t necessarily in an alarming or unsustainable position when considering some other factors. In fact, debt as a percentage of GDP has declined over the past five years, because nominal GDP has been growing faster than its debt.

Moreover, and unlike the UK or the US, Japan has a current account surplus – meaning that it’s a creditor to the rest of the world. It means that government borrowings are in a way offset by savings from the rest of Japan.

So, Japan’s government is not necessarily close to defaulting, nor should there be difficulty funding itself.

But that doesn’t mean that there are some worrying developments, especially for Japan’s bond market, and bond markets in general.

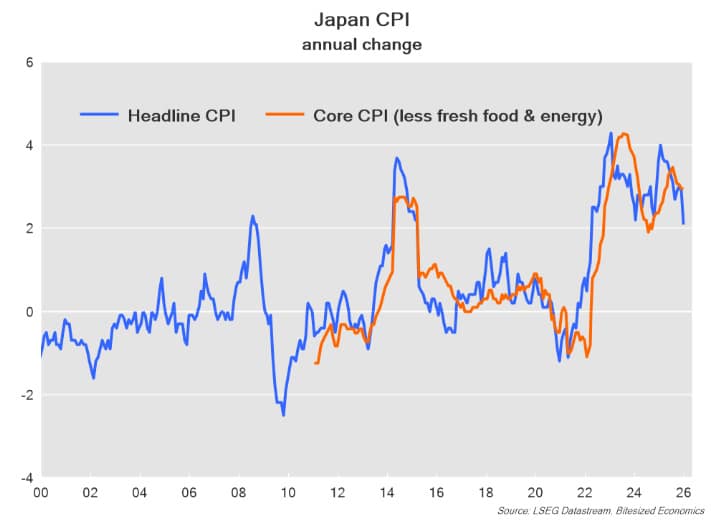

1) Firstly, there is a clear structural shift in Japan’s economy – the decades long deflation battle is likely over, and some inflation has returned.

At the heart of all of what is going on, is an emergence of inflation in Japan. Headline inflation has persistently held at 2% or higher for nearly four years now. And the realisation has sunk in for financial markets that Japan’s days of deflation are likely now behind us.

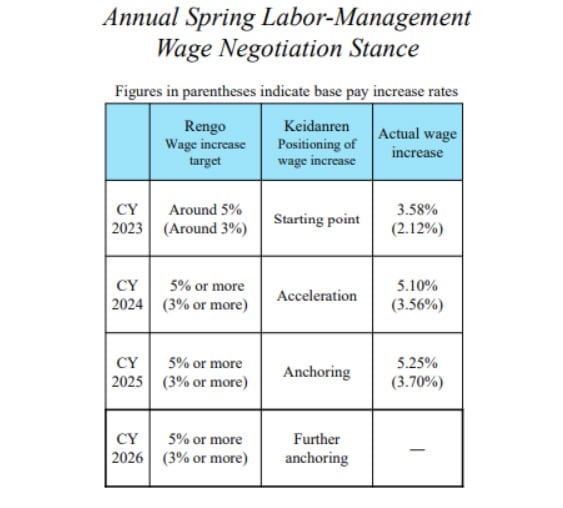

Most importantly, price increases have shifted wage-setting behaviour, and with some moderate inflation in place, that process is likely to continue. The below is taken from material used in a speech by Bank of Japan’s Governor Ueda on December 1:

Source: Bank of Japan

This is a structural shift in inflation dynamics. It also means that economic conditions alone do justify higher interest rates and bond yields, but that isn’t all that is going on here.

2) There are big liquidity problems in Japan’s bond market due reflecting the legacy of BOJ past bond purchases

That’s because of the BOJ’s yield curve control (YCC) introduced in 2016, capping the 10‑year JGB yield at 0%, with later adjustments. When global inflation surged during the pandemic and bond yields rose, markets expected rates worldwide to lift from zero. To maintain the cap, the BOJ had to buy ever‑larger quantities of JGBs, eventually owning 100% of a specific 10‑year issue and about 50% of the entire JGB market. Speculation intensified that YCC would have to be abandoned, especially after the RBA dropped its own YCC in November 2021 following a failed attempt to contain rising yields.

The BOJ ultimately kept yields near zero and exited YCC in 2024 with minimal disruption. However, its massive and prolonged bond purchases left the JGB market severely impaired: liquidity dried up, the market effectively disappeared for long stretches, and even post‑YCC the BOJ still holds a dominant share. This matters because a wide range of interest‑rate products and derivatives rely on a functioning JGB market for pricing.

3) Financial markets are becoming more vigilant when it comes to unfunded increases in government spending:

With inflation and rising interest rates, the question of debt sustainability changes. Higher interest rates mean a larger financing cost for the government. But the main problem is that Takaichi is proposing a sizeable tax cut, with no means of raising funds elsewhere.

Takaichi’s timing is especially poor. She wants to implement Abenomics-like policies when Japan isn’t stuck in a deflationary trap anymore. It is also at a time when bond investors have been more alert regarding the debt sustainability of governments. Inflationary environments aren’t the best time to ramp up fiscal spending.

In the May 2025 article, I wrote that Japan’s debt shouldn’t be problematic, unless inflation stays elevated. But inflation has persisted, and there is different prime minister who seems to be ignoring the traditional rules of fiscal discipline.

Implications

One lesson from the developments of the last week is that it is difficult to decide when markets will become jittery and when there is too much debt. It isn’t so much Japan’s debt levels are getting out of control, it’s that inflation has repriced the risk of that debt and the BOJ’s large scale bond purchases in earlier years have hindered the smooth functioning of the JGB market. That has led to volatility in other asset and markets.

In a nutshell, it would seem like the root issue is more of a liquidity issue rather than a solvency issue, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no concern about debt sustainability.

So, what happens now?

The US Treasury and Japan’s Ministry of Finance appear to be treating this situation like its just a liquidity issue that can be addressed with FX intervention to prevent the yen from weakening further.

But while intervention may provide a stop gap for liquidity issues, it isn’t likely to have a long-lasting effect if Takaichi continues with an unfunded tax cut, and over the more medium term, inflation remains elevated or accelerates.

Takaichi will need to find a way to fund the consumption tax cut elsewhere or risk the bond market would be at risk of being pummeled again. Expect more volatility in the lead up to the February 8 election, and there’s a high risk that the BOJ will step in to purchase bonds again, at least temporarily.