Recently, global asset manager T. Rowe Price held a webinar for Australian investors. I’ve transcribed part of the presentation by Emerging Market Bonds and Global High Income Bond Strategies Portfolio Manager Samy Muaddi whose role is exclusively focussed on debt markets. He describes how the world can get itself out of the third global debt wave…

Managing through financial repression

Financial repression is a period where monetary policy is deliberately kept at a rate below inflation. The reason you are concerned about losing money or losing in regards to duration is not a coincidence. It is a deliberate policy choice.

The first key assumption is that developed sovereign market debt cannot grow infinitely, solving this complexity is key for everything else you do. Whether it’s for bonds, the discount rate on your equities, or financing your property. So, solving for the risk free rate for sovereign bond rates is really an essential for success and your financial stability more broadly.

A heavily leveraged economy has only two ways they can get out of it.

- Government runs a primary surplus – revenue is greater than expenses, then you have the interest payments to service beyond that

- Maintain a positive differential between nominal growth and interest – Growth from productivity or inflation is needed

No other way to deleverage other than third world way seen in emerging markets – by defaulting

How has it worked historically?

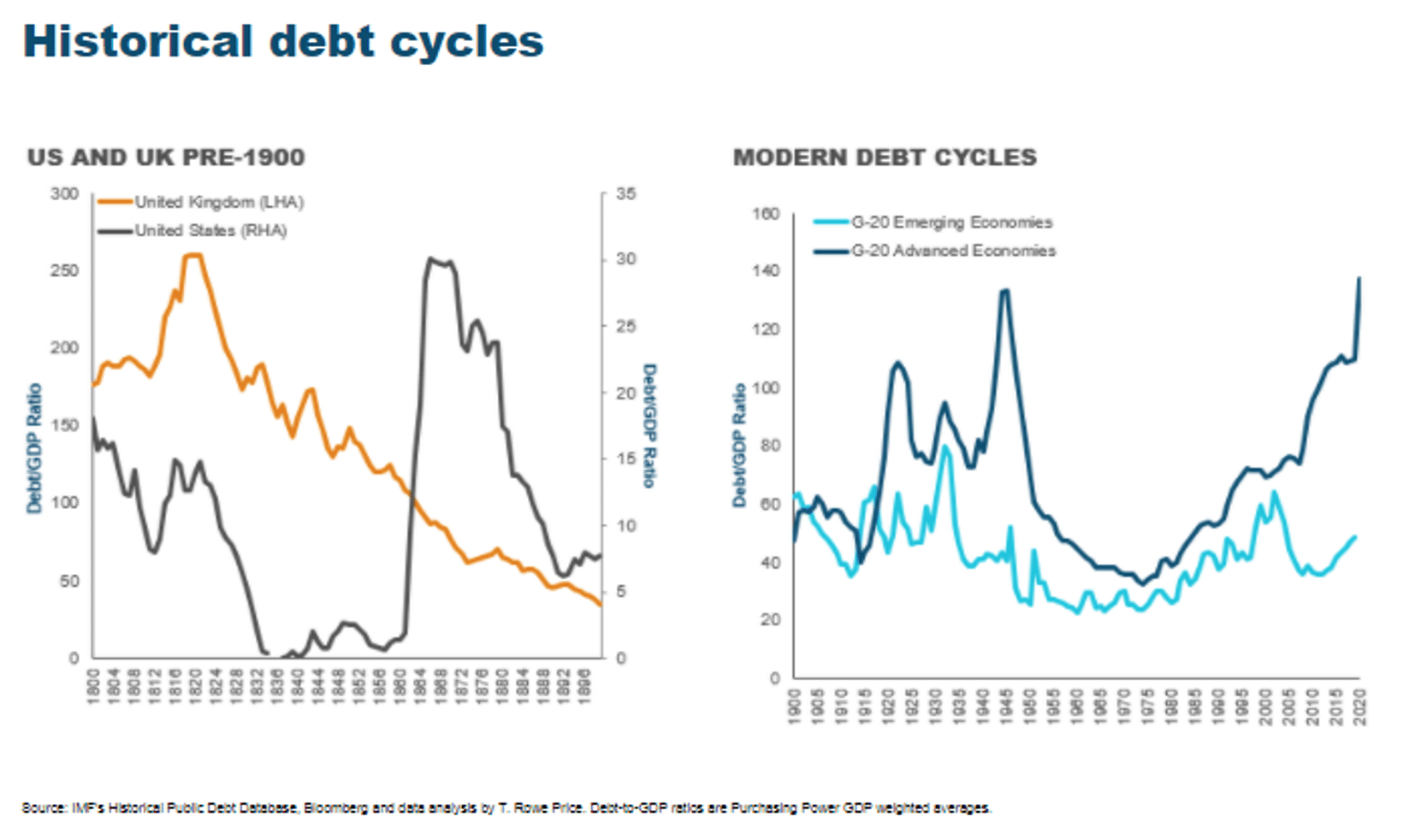

The bond market was founded just to finance wars and the biggest debt stock peaked around the Napoleonic wars in 1815 at the battle of Waterloo. After that the UK had a century of deleveraging. An excellent, disciplined and long 100 years of deleveraging, as shown in the first graph by the yellow line.

A lot of these circumstances inflect around pandemics or wars.

In the US, it was the Civil War then a period of deleveraging after that. Those are the historical debt crisis. On the right hand side is the modern debt crisis, focussed on advanced economies, including Australia.

I’m arguing we’re in the third great debt cycle, the first in the mid 1800s, the second being centred around the two world wars. So, if we can look at how the economies recovered historically, it can help us work out the path going forward.

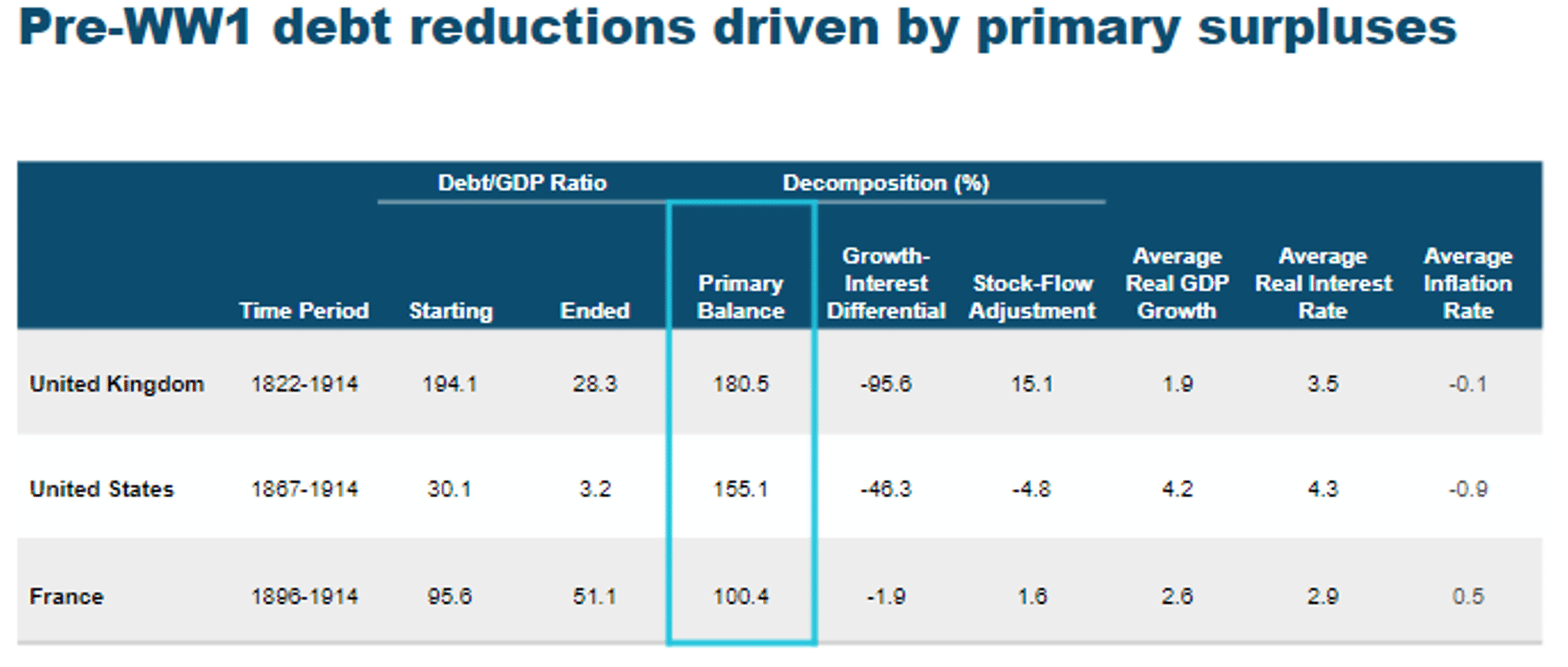

In the first great debt crisis, the UK debt to GDP ratio peaked at 194% and ended at 28.3% over 100 years later. How did that happen? It was the primary balance, circled in blue.

The politicians of the time were also the creditors and had learnt from the South Sea bubble and the Mississippi bubble of the 1700s. They were paying themselves quite well and if you look at the average interest rate and GDP, they were adding to the debt stock. To deleverage, the UK had two options and they chose the first option – fiscal discipline. The UK ran surpluses for 100 years.

Both the US and France also deleveraged almost exclusively through fiscal discipline. But these economies were not proper democracies and inclusive economies. The politicians were also the creditors, so had a vested interest in the deleveraging.

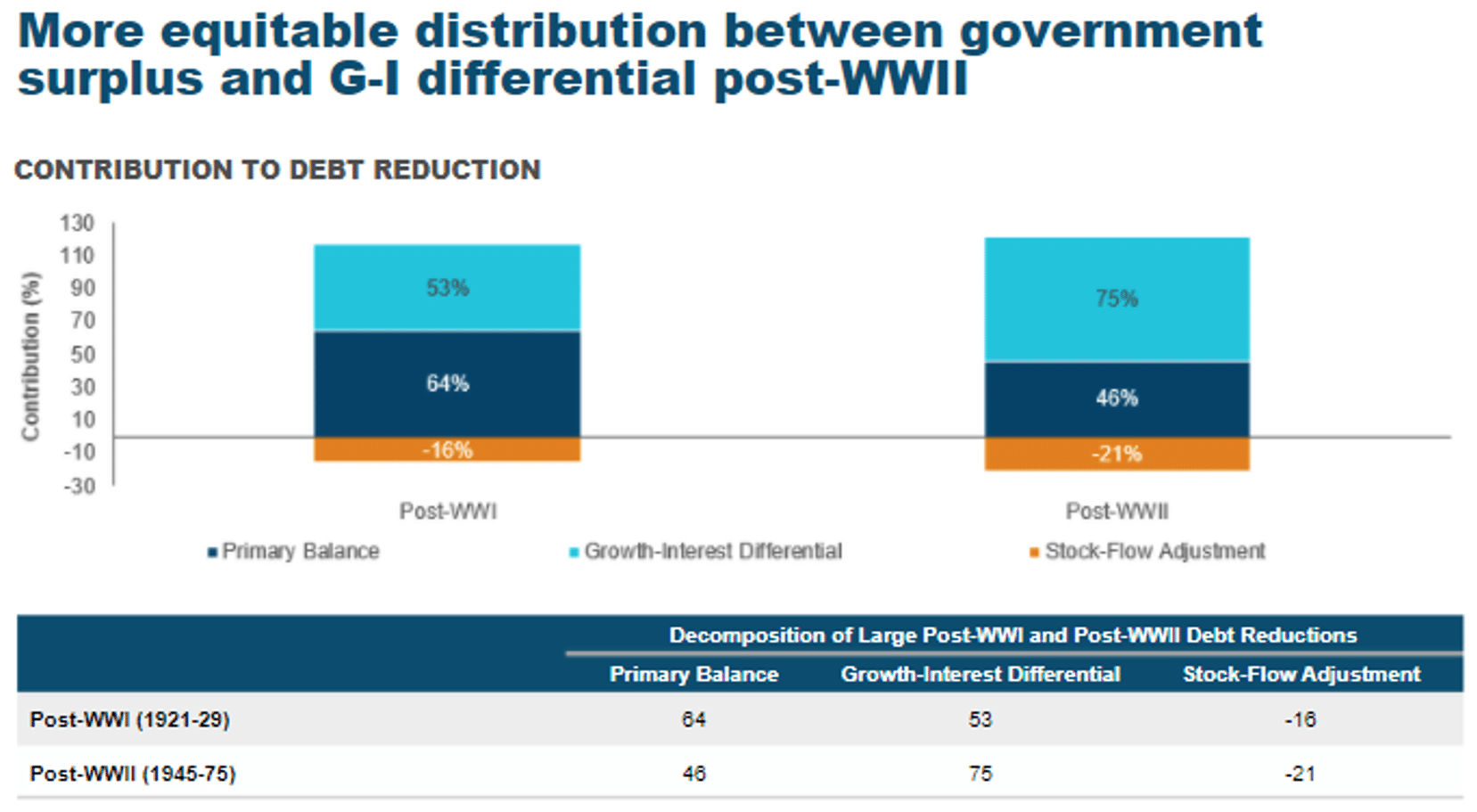

Moving on to the second debt crisis in the mid 1900s. What we have is almost an equal balance between the primary balance and the growth-interest rate differential. The great deleveraging was much more inclusive. Fiscal discipline was helped by a huge productivity boom and supportive population growth and some inflation along with that.

So, here we are at the apex of this big third debt cycle. We have two options, are we going to have fiscal discipline? When I read the newspapers, I see anything but that. Big stimulus packages, unfunded debt relief packages. From a social perspective, certainly warranted and society is demanding more of its governments. It’s a good thing and representative of a deepening of democracy. It’s hard to criticise but you still have to fund it.

Reserve currencies nations are abusing their privilege. They export paper and import real assets from the rest of the world. If you take that too far, history is not on your side. The abuse of the privilege undermines your ability to maintain it. That’s the real tension that’s happening in the developed market government bond world.

So, are we going to get out of this debt pile by running a primary surplus? I just don’t think the politics of today allow that. People and governments aren’t going to stomach the fiscal repression.

This brings me to the second option. This is the only way out of financial repression. The only way out of the debt stack is by growth to exceed interest, but we don’t have that productivity boom we had in the 1900s. So, we need inflation. I know my tone sounds negative but trust me, the alternative is worse. Our financial architecture isn’t built for deflation. So, looking at the history books and having average inflation targeting 2% plus, I think history will look back favourably because the alternative is much worse.

Our aim here is to manufacture inflation, to get nominal growth up to get that growth to interest differential to a point that a sovereign nation with a reserve currency can deleverage over a long period of time.

That’s the concept of financial repression and why it is happening.

What can you do about positioning you portfolio for financial repression?

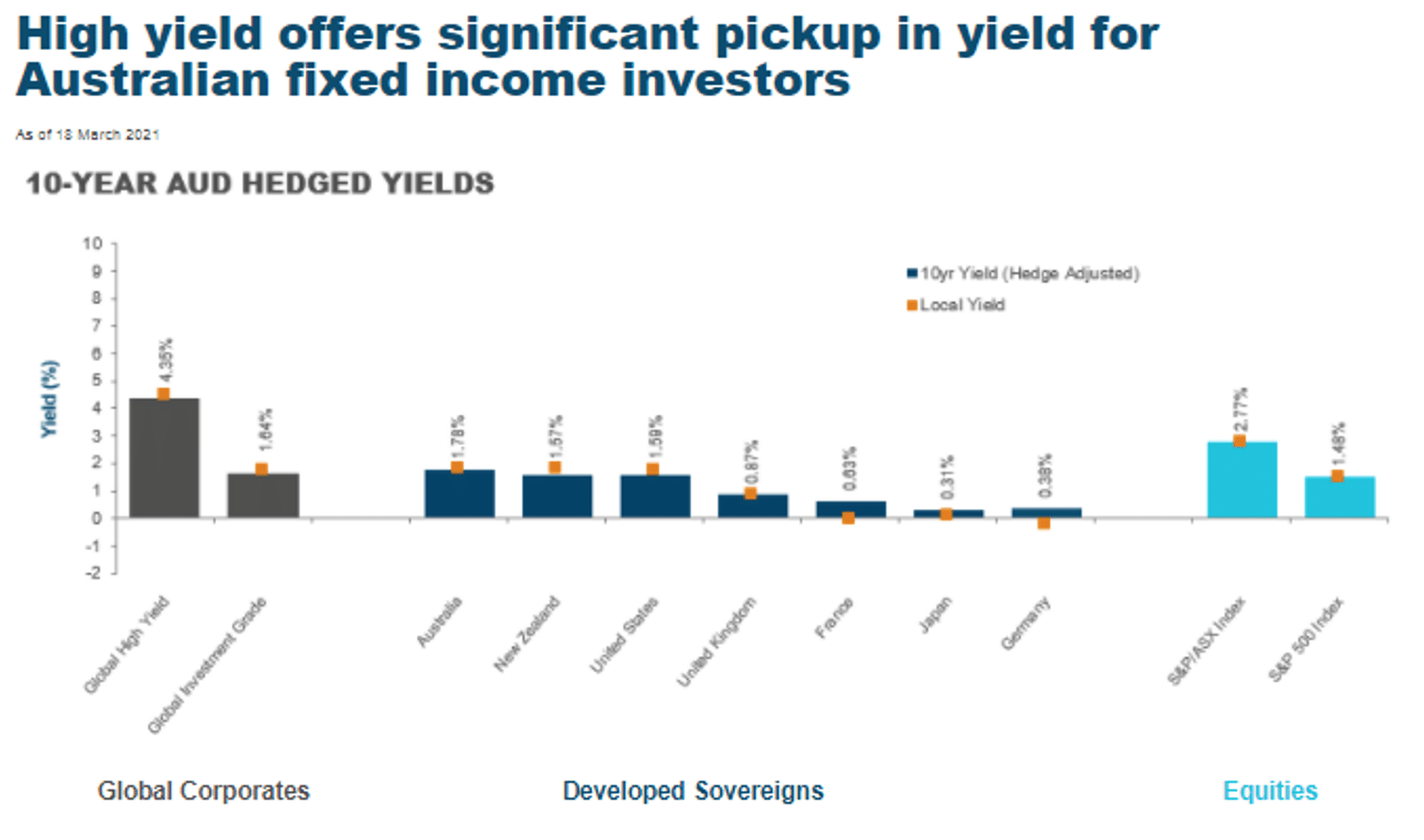

You have one option in fixed income and its high yield, the only other option is compound interest.

The graph below shows 10-year hedged yields. You can see on the left global high yield bonds showing 4.35% and our strategy is performing at around 5%. In the middle is a range of government bond yields in dark blue and the far right equity yields. That 5% global high yield bond return is really the last way for you to compound your way out of this period of financial repression.

Benefits of diversifying high yield are many:

- European and EM HY markets has less than half CCC exposure that the US has

- Can diversify HY while deflating volatility profile

- Never lost more than 1% in a year in HY, probably our proudest achievement

Back to compounding, you can’t compound with big drawdowns (losses). So, casting a wider net and avoiding the CCC rated credits is a way to ensure the income by preserving capital in the down market.

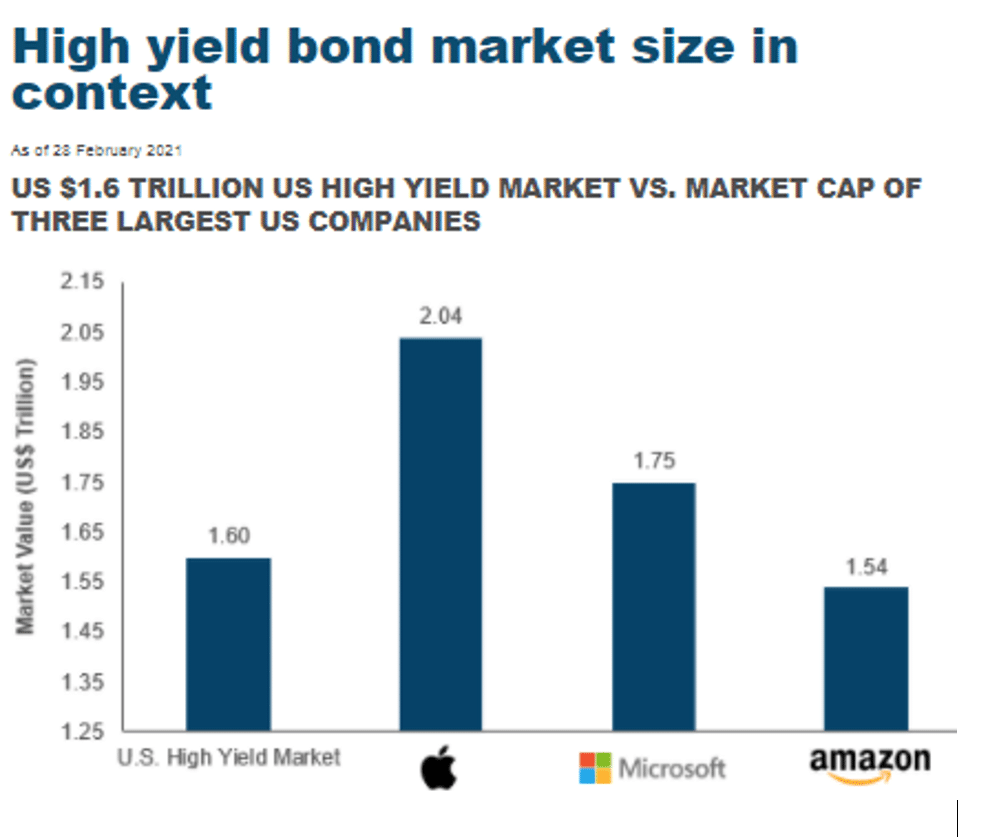

If you are interested in HY bonds, there are not enough of them to go around. The market isn’t growing enough. In the chart below I plotted the market cap of the three largest US companies – Apple, Microsoft and Amazon and the size of the entire US High Yield Bond Market is less than the two largest companies and way less than the three companies combined.

In terms of Apple, the average daily turnover of the stock is higher than the average daily turnover of the entire US High Yield bond market. This has never happened before in history. So even with a fraction of equity de-risking and going into high yield, there just isn’t enough to go around. What happens with financial repression is the volatility of the asset gets deflated, so the European high yield market, after Europe went into financial repression, the BB rated credits spent 80% of its time below a 3% yield.

We’ll still have a credit cycle and defaults will happen but your trading volatility on the asset given this dynamics is not something you should be using historical data on.

Key Points:

- Developed sovereign debt cannot grow indefinitely

-Solving for yield levels is key for financial markets - Two ways to deleverage an economy

- Currently leading up to a third major debt cycle

- Populist pressure means government surpluses are less likely

- Compounding interest through higher yielding assets could be the only way out for investors

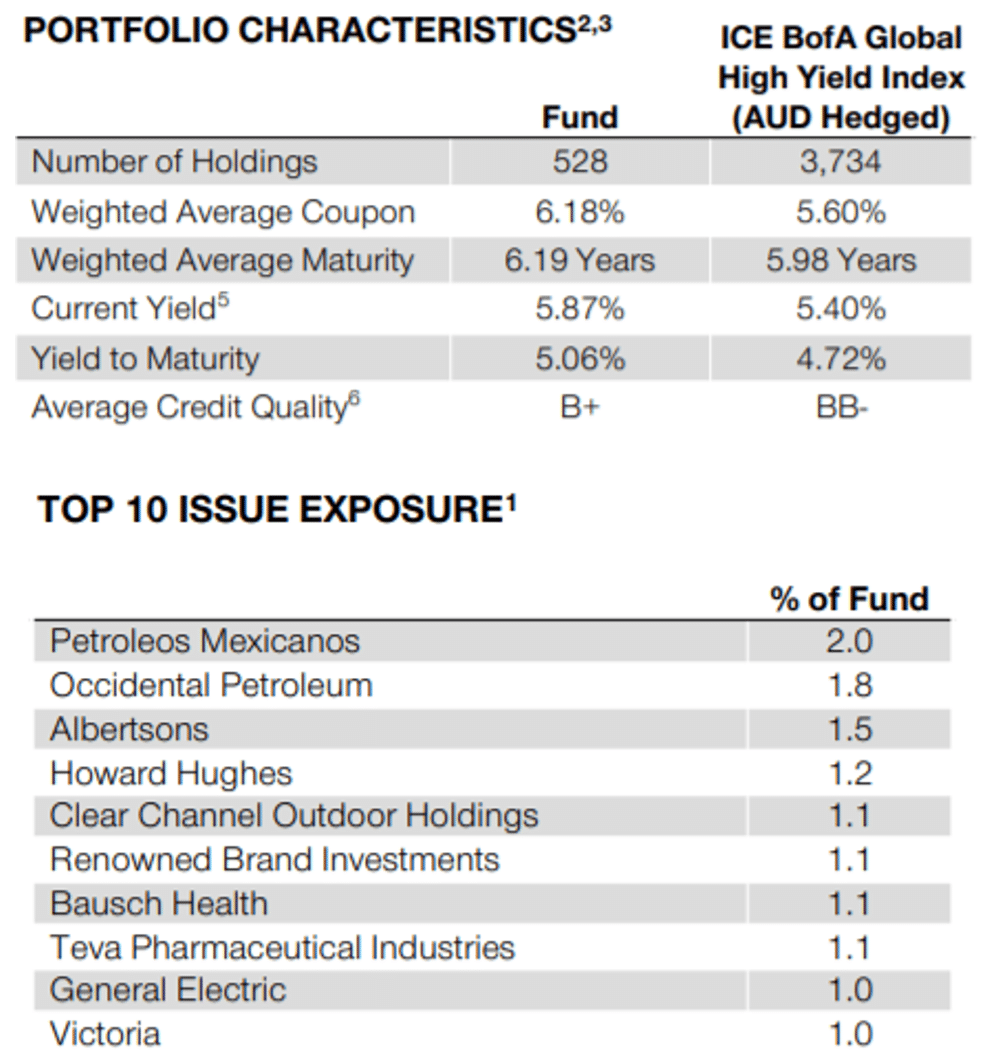

Note: T. Rowe Price has the Dynamic Global Bond Fund and the Global High Income Fund available to Australian investors. The High Income Fund commenced 4 May 2020 and its return since inception is 18.16%. As at 28 February the fund characteristics are stated below.