By Haran Karunakaran, Investment Director at Capital Group

Key takeaways

- The last few months have seen a significant change in the macroeconomic environment. Policy rates appear to have peaked and central banks around the world are gradually looking toward a period of rate cuts.

- This shift from hiking to cutting will likely have significant implications on market returns for months and years to come. History suggests it will be negative for the large cash allocations that many investors hold today, with rate cuts transmitting directly into a rapid decay in cash yields.

- By contrast, these inflection points have historically been positive for high-quality bonds, which see outsized capital gains from yields falling.

- The current environment provides the chance for investors to bolster their defensive allocation and take advantage of a rare opportunity in high-quality bonds.

The last few months have seen a significant change in the macroeconomic environment. A resilient consumer has helped support economic growth in the US and elsewhere. At the same time, inflation has taken a pivotal move downwards. Significantly, this pivot has also been seen in the stickier components that had previously stayed stubbornly high. Consequently, the market debate has shifted from “how many more rate hikes?”, to “when (and how aggressively) will central banks cut rates?”.

In December 2023, the US Federal Reserve’s latest dot plot (the interest rate projections of individual Federal Open Market Committee [FOMC] members) showed 75 basis points (bps) of cuts in 2024 and a further 100bps of cuts in 2025. While week-to-week we see volatility around market expectations for inflation and interest rates, the Fed and many other central banks have clearly signalled an intent to bring rates down over the next few years.

Historically, these pivots in monetary policy have significantly impacted market returns and, as such, warrant a rethink of investors’ defensive allocations.

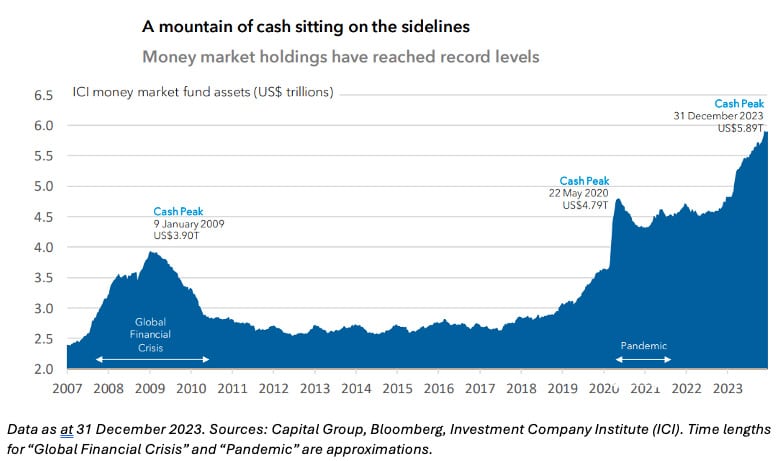

A striking asset allocation trend over the last few years has been a significant build-up of investors’ cash balances. US money market fund assets have doubled since pre-COVID days to reach almost US$6 trillion today; if term deposits and other cash alternatives are also included, the number would be even higher. And this is not just a US trend. Many other countries around the world have also seen large increases in the allocation to cash.

In the right circumstances, outsized cash allocations can serve as an effective defensive ballast in portfolios. The heightened volatility of 2022 illustrated this well. Then, both equity and fixed income markets simultaneously delivered negative returns (for the first time in almost five decades) and cash stood out as the rare asset class that delivered positive returns. However, just one year later, markets provided the opposite lesson, with cash materially underperforming fixed income in 2023.

Also read: Can US Government Bonds Withstand the Growing Mountain of Debt?

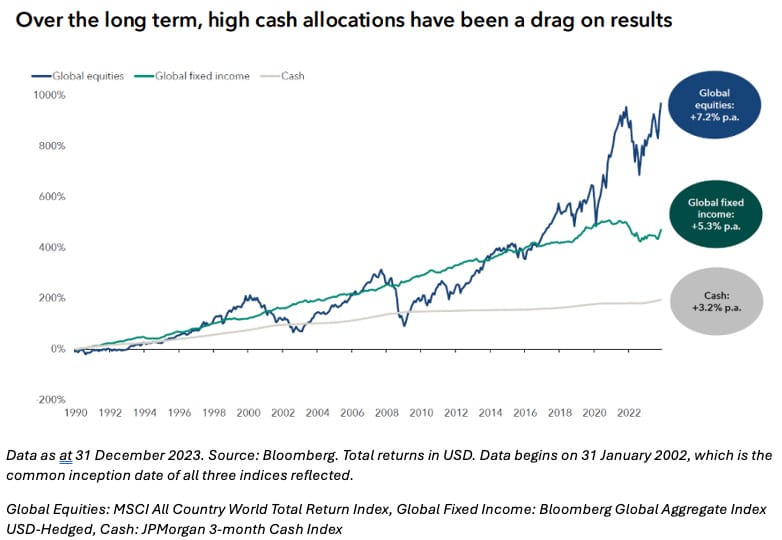

Cash is a defensive tool best used tactically… and sparingly. Over the long term, cash has clearly underperformed bonds – persistent outsized allocations to cash can leave significant returns on the table.

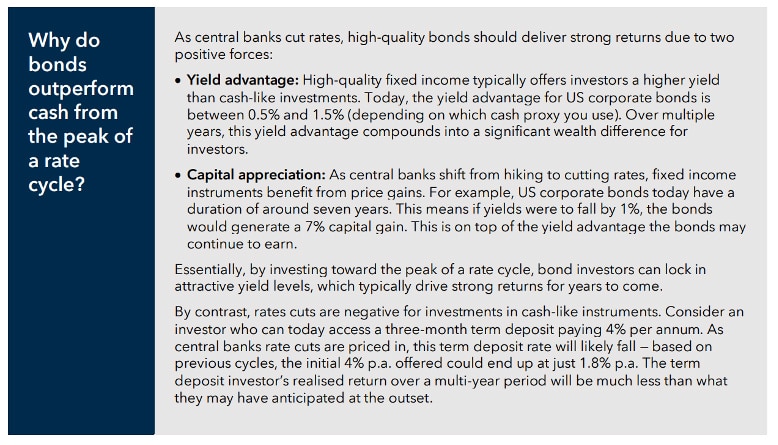

Investors should be asking themselves whether this large build-up of cash still makes sense. The macro environment has changed significantly. As inflation eases and central banks move toward rate cuts, the benefits of maintaining such high allocations to cash may be diminishing. On the other hand, high-quality bonds can provide that ballast, while also seeing stronger returns as bond prices rise with falling rates. In other words, this is an environment where it may make sense to shift back toward a more traditional defensive bond allocation.

Lessons from history

Historical analysis can provide useful guidance on how bonds and cash perform through different parts of the market cycle. As 2022 illustrated, a rising rate environment is bad for bonds; investors were clearly much better off in cash. But as rate cycles around the world move towards their peak, are we at an inflection point where it makes sense to shift back into fixed income? History would suggest the answer is yes. An analysis of every sustained US rate hiking cycle since the 1980s1 highlights some interesting patterns.

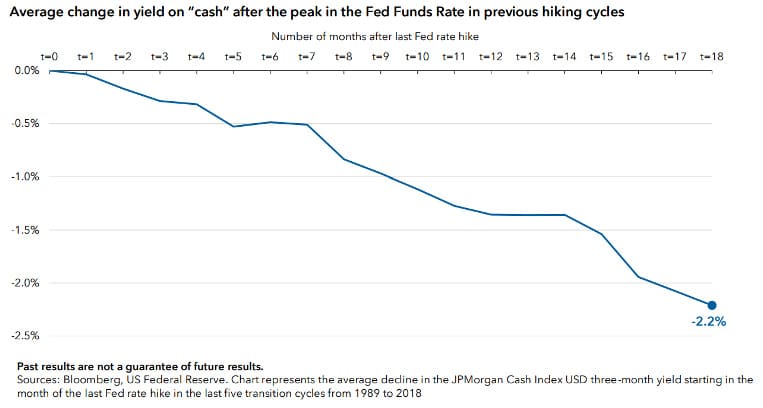

1. “Cash” yields decay quickly after the peak in Fed Funds rate

The first point to note is that yields on cash-like instruments have tended to decay very quickly following the last interest rate rise of a hiking cycle. Over the last five rate hiking cycles, the JPMorgan Cash Index USD three-month yield was an average of 2.2% lower 18 months after the last Fed hike. This is because central banks typically cut rates quickly as inflation declines and, in some cases, to dampen potential economic slowdowns. These cuts transmit directly to cash yields (as well as to other floating-rate instruments such as term deposits, floating rate corporate bonds and much of the loans and private credit market). Cash investors are forced to reinvest into lower and lower rates, resulting in materially lower returns than they may expected at the start of the cycle.

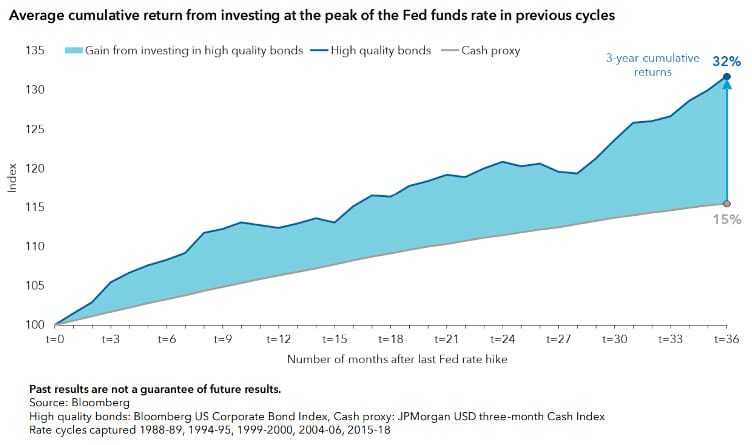

2. The end of a rate hiking cycle is good for bonds

High-quality fixed income has, on average, provided stronger returns than cash-like investments following the peak of a rate cycle. Over a three-year timehorizon, high-quality bonds (proxied by the Bloomberg US Corporate Bond Index) delivered, on average, a cumulative return of 32%. That is double the average return on cash (proxied by the JP Morgan USD three month cash index) – an exceptional result for a very high quality and defensive asset. The turn in the interest rate cycle provides a rare return opportunity for high-quality bonds.

What happens after policy rates peak?

3. Time in the market matters

The back end of 2023 saw a signficant rally in bond markets, with US Treasury yields declining around100 bps in the space of a few weeks (bond prices move inversely to yields, so this generated capital gains for bond investors).

Does this mean investors have missed the opportunity in bonds?

For me, the answer is a clear and resounding no. Certainly shifting from cash to bonds ahead of the rally would have been better. However, aiming for that sort of precise market timing can be a fool’s errand.

What matters more is “time in the market”. The inflection in monetary policy that we are on the precipice of – from one of the most aggressive rate hiking cycles in history to a more normalised interest rate environment appears – likely represents a structural, multi-year change. One that history would suggest should provide long-term support to bonds.

Analysis of previous cycles, highlights bonds deliver significantly higher results compared to cash for more than three years. In other words, there is still a long way to go and what really matters is not whether you managed to catch the peak, but ensuring your asset allocation is aligned with the underlying macroeconomic environment. Ultimately, what matters most is time in the market as this long-term trend plays out.

How bonds play defence

Bonds traditionally have some key defensive roles in a portfolio:

- Diversification from equities. High-quality bonds have historically tended to provide good diversification from equities. By allocating to such bonds, volatility can be dampened and a more durable portfolio built.

- Capital preservation. High-quality bonds can provide a degree of stability over time. Historically, such bonds have demonstrated a strong track record of protecting capital.

- Bonds provide an explicit and predictable income stream, so long as the issuer remains solvent. This can help absorb periods of price of volatility and maintain total returns.

The rise in yields over the past two years means levels of income within high-quality bonds is now much higher, and consequently, investors no longer need to reach for yield to achieve their income objectives. This means that by allocating to higher-quality bonds investors now have greater capacity to diversify risk without needing to sacrifice yield.

Implications for investors today

As investors think about the defensive portion of their portfolios, there are two key points that should be kept in mind.

First, the defensive allocation is more important today than it has been in many years. We are in a macro environment of elevated risk, whether that be recession concerns, geopolitical tensions or election-related volatility.

Investors once again will need to lean on their defensive allocations to provide stability for their portfolio; the traditional role of bonds is back. High-quality fixed income can provide investors with key defensive characteristics, namely capital preservation and diversification against equity market volatility.

Second, the current environment provides a rare return opportunity for bond investors. Bond yields remain near decade highs; investing today allows investors to lock-in these returns for years to come. If central banks do cut rates over the next few years, this would provide an additional (and likely significant) tailwind for bond returns. By contrast, a falling rate environment would be negative for cash allocations as rate cuts immediately pass-through to a decaying cash yield.

The outlook for high-quality fixed income today is more exciting than it has been in many years. History tells us that the expected inflection in monetary policy will lead to diminishing returns for cash but provide a very positive environment for high-quality bonds. Is now the time to make this shift? I believe the current environment provides the chance for investors to take advantage of a rare opportunity in high-quality bonds to bolster their defensive allocation.

Haran Karunakaran is an Investment Director at Capital Group. He has 18 years of industry experience and has been with Capital Group for two years. Prior to joining Capital, Haran worked as a senior vice president and fixed income strategist at PIMCO. He holds an MBA from London Business School and a bachelor’s degree in commerce, majoring in finance and economics, from University of Sydney. He also holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation. Haran is based in Sydney.