By Richard Quin, CIO and Principal, Bentham Asset Management

October 2022

Fund structure plays an important part in the performance of credit funds. A well-structured fund supports pricing transparency, liquidity and fairness for unitholders. This series by Richard Quin from Bentham Asset Management discuss fund attributes. We published Part 1 recently, outlining what a well-constructed, open-ended credit fund should look like.

Here, we pick up the list of lessons to be learned from historical examples of funds that have failed investors through poor credit portfolio construction.

3. Non-rated or shadow rated securities

Applying a public rating to a bond or loan broadens the marketability of that security as many types of investors require a rating from a recognised rating agency1 to allow inclusion in a portfolio.

A public rating of corporate debt (compared to private debt) ensures a reasonable amount of information is available and has been reviewed by an independent third party.

Domestically, most (investment-grade) bond issuance is rated, but few loans are rated. By contrast, 95% of the US Broadly Syndicated Loan market is rated.

When assessing what proportion of a fund’s assets are ‘rated’, it is important to distinguish between an internal rating (determined by a fund manager, and of use only inside that institution) and an external rating from a recognised rating agency. When publishing a “% rated” statistic, we believe managers should be absolutely clear about the type of rating they are referring to.

Key Takeaways:

- A public rating improves marketability of debt, which improves liquidity.

- Unrated debt is less common overseas.

- Private debt offers less information transparency.

- Internal ratings may have a qualitative bias to be higher, particularly if based largely on financial ratios. External ratings are based on both qualitative and quantitative factors.

4. Liquidity = Marketability

The marketability of an investment supports liquidity in that instrument. The relative size of an investor’s holding and the depth of a market (in terms of trading volumes, and number of participating investors) are key determinants of the liquidity of debt. Desirable investments usually have good market depth near the current price.

The characteristics of marketability include:

- Broad distribution (by investor type) which should lead to superior liquidity.

- Transparent pricing, including observable bid/ask spread.

- Rated entity (with preferably two ratings) providing a handle for relative value comparison.

- No locally-specific tax benefits (i.e. franked securities are marketable only within Australia)

- A genuine secondary market with sizeable flows. An ASX listing, for example, can give a false impression of liquidity by generating frequent pricing information, but with limited volume.

Investors in illiquid/private debt are married to debt with little possibility of divorce. It greatly restricts the ability for a Portfolio Manager to respond quickly to advantageous investment opportunities that may be presented in the market. It also restricts the ability of a portfolio to be managed and re-weighted to take advantage of these opportunities.

Key Takeaways:

- When assessing public and private debt investment opportunities, investors need to consider the relative marketability and liquidity of each.

- Private debt has less marketability and is therefore less liquid.

- A listed market for securities does not guarantee meaningful liquidity.

- Illiquid investment requires an illiquidity premium (fees, higher spread, etc).

5. Marketability of assets reduces fund lock-up risk

Lockup of a fund (the suspension of redemptions) may occur when a manager believes there is no liquidity to sell into, or that the price available in the market doesn’t provide value to investors. When a Fund contains assets which are not marketable, a manager may be forced to resort to lock up.

6. A listing cannot ensure fund liquidity (only an active pool of investors can)

Just as a listed market does not guarantee liquidity for individual securities, listing an investment vehicle (e.g. a LIC) cannot create liquidity for fund investors. In practice, a LIC may trade at a large discount to NAV if investor demand for the vehicle is low (i.e. liquidity is poor).

7. Diversification is important

A key concept in credit portfolio management is diversification. This is because defaults tend to be unexpected and occur in industry clusters. The more recent sell off in credit (over 2022) has been caused by systemic risk aversion and has not impacted funds that have concentrated portfolios. However, when defaults increase, the lack of diversity can become a significant issue for funds holding concentrated positions in less liquid markets (e.g. the Energy sell-off in 2015/16).

We observe that in a global context, Australia is unique in tolerating concentrated credit portfolios despite our economy facing the same default risks as elsewhere. For example, investment grade Australian corporate credit portfolios are often concentrated in bank issuers, while Australian private debt funds often focus on the domestic real estate sector.

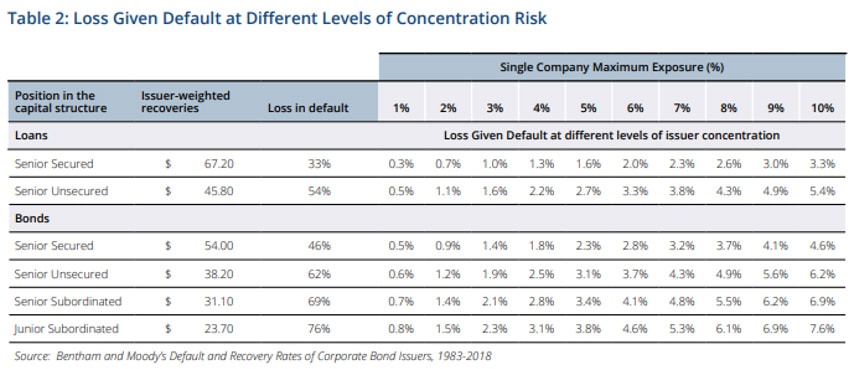

The below matrix shows the loss given default (LGD) of different issuer concentration limits. Not surprisingly, the LGD increases in a linear fashion. E.g. a 10% concentration is 10 times riskier than a 1% concentration.

Moody’s has a measure of portfolio diversity called a Diversity Score, which is their primary measurement for industry and issuer diversification in CLOs (Collateralised Loan Obligations). This score recognises that diversification by number of issuers is not sufficient. In essence, increasing the number of industry exposures increases the diversity score, as can different country exposures.

Diversity is more important in credit portfolios than in equity portfolios but less recognised. This is due to the asymmetric returns of credit portfolio. A portfolio with 20-50 securities is not diversified enough to reap the full diversifiable benefit. Investing in a credit fund with only an equity fund level diversity requires exceptional confidence in the investment managers’ expertise.

Table 2. Loss Given Default at Different Levels of Concentration Risk

Key Takeaways:

- Strict industry and issuer concentration limits are important in decreasing the overall losses when defaults do occur.

- In a higher default environment, portfolios with higher concentrations will suffer more per individual default.

- Different industry and country exposures create diversity.

- A credit fund should be much more diversified than an equity fund.

8. Holding a substantial proportion of a single issue (cornerstone investors / club deals)

While holding greater than 20% of a security may give an investor power to drive lending terms, so-called cornerstone investors generally (by definition) also reduce the breadth of investor distribution. This not only places great emphasis on the initial credit research but also implies that the cornerstone investor will have limited ability to efficiently exit their holding if the credit quality of the security deteriorates. A restructure is generally required.

The 2008 crisis proved that the type of investors who invest alongside you matters. Should other investors in a small club deal be forced to sell into difficult market conditions, the remaining holders could experience a sharp fall in price without there having been credit impairment. Having a closed-end fund to reflect the underlying liquidity of the cornerstone/club investments may be important.