By Sam Morris, CFA – Senior Investment Specialist, Fidante Partners & Pete Robinson, Head of Investment Strategy and Portfolio Manager, CIP Asset Management

Interest rates have decreased dramatically over the past decade and fixed income returns have declined in tandem. Some of these changes may unwind as we enter a world of higher inflation and withdrawal of central bank stimulus measures over the coming years, but other changes are much more structural in nature.

A fast-growing Australian private debt market is stepping in to satisfy investor’s needs for higher yielding fixed income investments.

In particular, regulations requiring banks to hold more capital are likely to persist, causing banks to withdraw from certain types of lending and reducing commitments to public credit markets during times of stress.

As such, institutional and retail investors are investing in private debt markets alongside traditional public credit allocations to boost returns. Private debt is a complex asset class that can offer a differentiated opportunity set with unique return, risk, liquidity, and diversification benefits.

Distinguishing between Public and Private Debt

Private credit is often also referred to as “direct lending” or “private lending” or even “alternative credit.” Irrespective of the name, they are basically loans to borrowers originated directly by a non-bank asset manager rather than via an intermediary.

Also read: The Debt Owed Per Head Of Every Australian

Unlike traditional bond issues or even syndicated loans (such as US term and leveraged loans), there is little intermediation between borrower and lender. The lender basically arranges the loan to hold it, rather than originating to sell it. As such, the borrower and the lender have a much closer and more transparent relationship, directly negotiating the terms of the finance.

In a recent Economist magazine special report on the asset management industry, one of their concluding forecasts was that private debt would become an increasingly important asset class. As the Economist notes, “The growth of private debt is, in large part, a response to the retreat of banks from lending to midsized businesses and their private-equity sponsors. Asset managers, starved of yield in the government-bond markets, are happy to fill the void.[1]”

LISTEN: Private Debt with Andrew Lockhart – Managing Partner of Metrics Credit Partners

Private debt is now a significant subset of broader credit markets globally. Underlying exposures include private loans to mid-size or non-listed corporates (often backed by private equity sponsors), commercial, industrial and residential real estate loans that sit outside the risk appetite of the banking sector, as well as loans secured by securitised assets such as mortgages, other loan receivables (particularly from non-bank lenders) or ‘alternative’ cashflow streams such as royalty streams, insurance premiums or solar panel lease payments.

A key distinction—and advantage—across many types of private debt is the ability to customise lending terms, thus exercise greater control over credit risk protection compared to public markets. Private credit investors can influence or dictate elements such as coupon and principal payment schedule (amortisation), loan covenants, information access and control rights, tailoring investments to their desired liquidity, return and credit risk profile.

By not introducing an intermediary to arrange the transaction, the fees otherwise paid to the arranger can be shared between borrower and lender, enhancing the overall return profile of the investment relative to syndicated transactions.

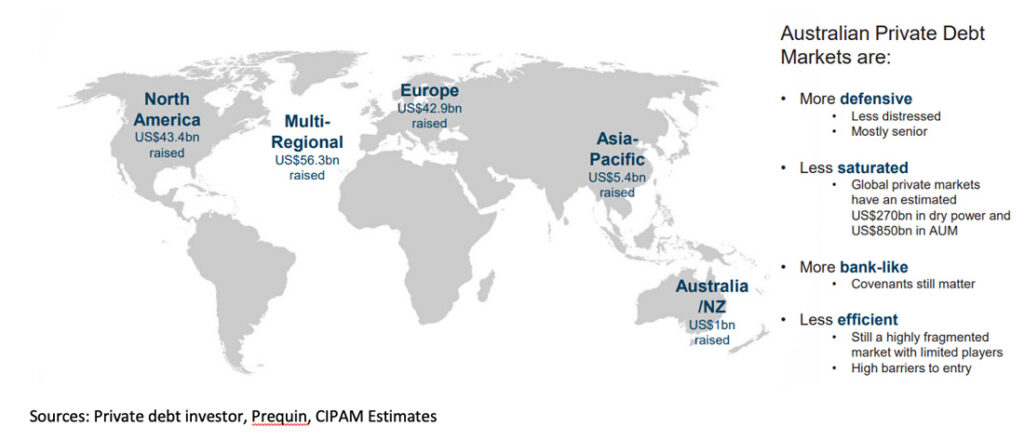

Australia remains a relatively promising market compared to offshore growth in private debt assets and corporate credit generally. But this comes with significant advantages due to the lack of competition from asset managers bidding down yields and credit protections to obtain deal flow means that underwriting standards and margins remain strong.

Australian private debt in a global context – 2020 Fund Raisings

What is the Illiquidity Premium and Why Does it Exist?

Any risk premium in investing can be thought of as a transfer of economic rents from risk avoiders to risk takers. In equities, for example, there is a strong, academically established risk premium for investing in small cap companies. This is because these stocks often have less liquidity stemming from their lower overall market capitalisations and lower free float for external shareholders as well as less diversified revenue streams and/or robust balance sheets.

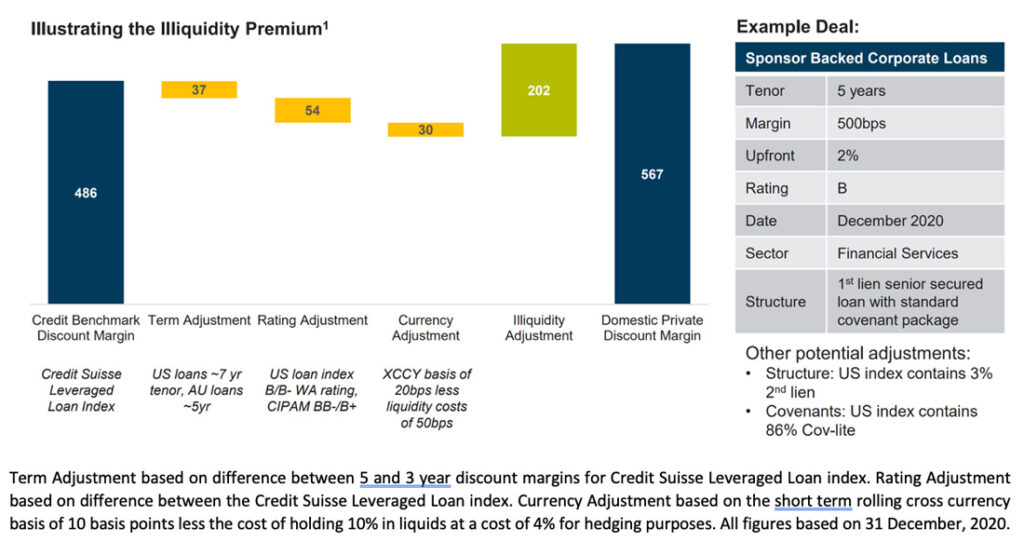

In many respects, similar arguments can be made for a higher rate of return for private debt compared to public credit. The simple explanation is that private debt arrangements do not have the structural features of public credit such as official credit ratings, combined with security identifiers and legal structures that enable centralised clearing and settlement and thus easy trading.

This means that borrowers who obtain financing from such sources must pay a higher interest rate for a given level of implied credit risk to lenders, who need that higher rate of return to justify their reduced flexibility in managing their investment. Thus, by comparing the rate paid between private debt and public debt at the same assumed credit rating or risk level, we can estimate a proxy for the value of the illiquidity premium.

[1] Taking back control | The Economist

This material has been prepared by Challenger Investment Partners Limited (ABN 29 092 382 842, AFSL 234 678) (CIPAM). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information.

Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable but are subject to change and should not be relied upon.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.