By Sonal Desai, Ph.D. Chief Investment Officer, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

Bond investors have started the new year on a very upbeat tone. They seem convinced that the battle against inflation has already been won. The Federal Reserve (Fed) might nudge rates up a bit more to stay on the safe side, but soon enough we’ll go back to a world of very low interest rates—this seems to be the consensus view based on the price action.

The encouraging US December Consumer Price Index (CPI) print solidified this view—headline inflation fell 0.1% from the previous month, pushing the year-over-year rate down to 6.5% from November’s 7.1%. Core inflation (excluding food and energy) slowed to 5.7% from 6.0%. Mission accomplished?

I believe not. I think markets are still too optimistic on inflation, and underestimate a very important shift in central banks’ attitudes. In this post I will summarize my thinking in four points.

First. Macro policies are still relatively loose.

It’s true that supply shocks are fading out, rent inflation will likely soon peak, and there is some weakening in economic activity. But this weakening is nowhere near enough of what’s needed to pull inflation down to 2%–3%, because there are a number of inflationary forces still at work. In particular:

a. Fiscal policy remains very loose; we are looking at a fiscal deficit in excess of 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) with a relatively robust economy; on top of this, Congress passed a US$1.7 trillion funding bill that increases discretionary spending by 6%.

a. Social Security and disability checks have just increased by close to 9% for 70 million people—that’s close to 30% of the adult population.

b. The Fed’s balance sheet is still way larger than pre-crisis, with an expansionary impact on monetary policy.

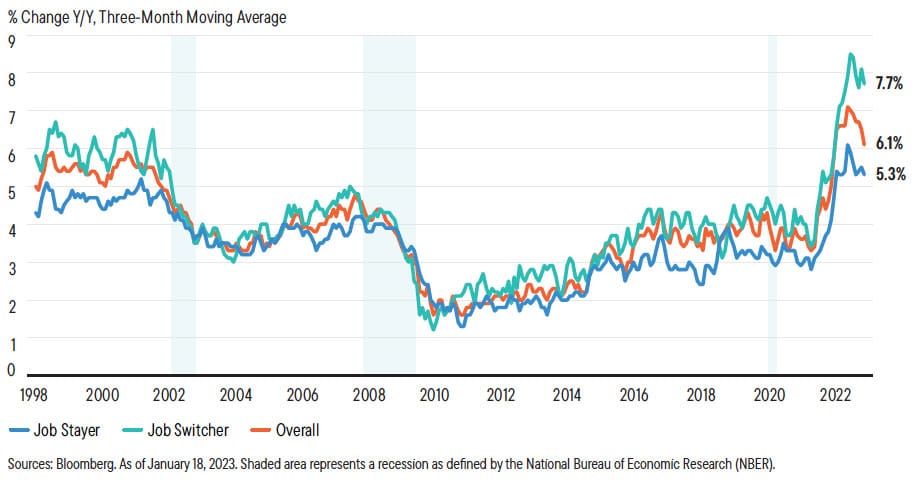

Second. I think markets and many analysts have a “glass half-full” view of wage growth and inflation expectations:

a. We have different measures of wage growth, and some show an encouraging decelerating trend. But others do not. The latest available data from the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker show wage growth treading water at a rather elevated level. In December, wages for workers switching jobs rose 7.7% year over year; but wages for workers staying in their jobs also increased a hefty 5.3%, showing that employers are having to give robust wage raises to retain workers.1 Overall wage growth increased 6.1%.

b. We keep hearing that long-term inflation expectations are still well anchored, and indeed the New York Fed survey of consumer expectations has five-year ahead expectations just over 2%.2 But one-year ahead expectations are 5.2%. Inflation has run above 5% for a year and a half already, and consumers expect it to stay above 5% for another year. To me that means that while consumers do believe that eventually inflation will come back to target, for the time horizon relevant to most of their economic decisions, they expect inflation to remain much higher.

To summarize, we have a strong US labor market with the unemployment rate still at 3.5%, wage growth running at 6% and one-year ahead inflation expectations above 5%. It seems very unlikely that we can halve the inflation rate by the end of this year with just a reduction in job openings. I think we are more likely to end the year with inflation at 4%–5%.

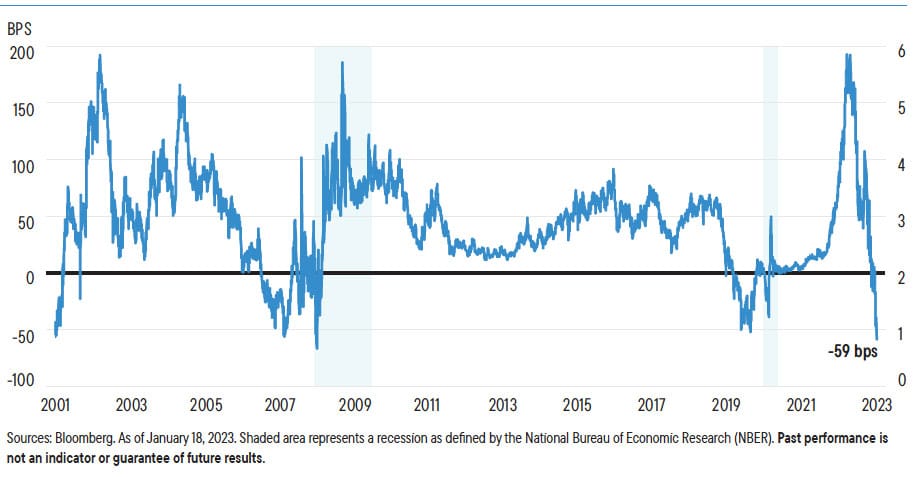

Inversion in the Yield Curve Suggests Bond Markets Expect the Fed to Pivot Soon

Exhibit 1: Two-Year US Treasury Minus Three-Month US Treasury Yield Spread

January 2000-January 18, 2023

Third. Financial conditions remain loose, and this could turn the markets’ confidence in lower rates into a self-defeating prophecy.

Markets keep testing the Fed. The Fed keeps promising that it will hike more and then keep policy tight for quite a while. Markets bet that as soon as growth weakens a bit more the Fed will blink and start cutting rates. But as looser financial conditions offset part of the Fed’s tightening effort, the central bank runs a higher risk of inflation pressures becoming entrenched at an uncomfortably high level. This cat-and-mouse game is one reason why I think the Fed will have to raise the policy rate to 5.00%–5.25% and leave it there for the remainder of this year.

Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker Pointing to Still-Elevated Wage Pressures

Exhibit 2: Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker

January 1998-December 2022

Fourth and most important. I believe financial markets are misguided in thinking that central banks will end up regarding this inflation episode as simply a temporary aberration.

Just like the global financial crisis (GFC) caused a long-lasting change in the attitude and stance of monetary policymakers, the inflation surge of the past couple of years will have a similar long-lasting effect.

The GFC did not result in a new great depression. But central banks became nonetheless much more sensitive to the risk of deflation, and for the next 10 years reacted to every shock with an overwhelming monetary easing. Similarly, the recent inflation surge will not result in hyperinflation or even in a 1970s-style inflation spiral, but it will make central bankers much more sensitive to the risk of entrenched higher inflation. Central bankers now understand that prolonged loose monetary policy contributed to a multi-year inflation overshoot that they have not yet brought back under control. You can see it in statements from monetary policymakers in both the Fed and the European Central Bank. As a consequence, as the economy slows and possibly dips into contraction, central banks will not rush to pull all stops, driving rates to zero and launching a new stage of quantitative easing. I think they will instead limit themselves to more traditionally sized rate cuts.

This is reinforced by another consideration: over the past decade and a half, central banks could rely on important disinflationary forces, especially the surge in labor supply from China and deepening global supply chains. These forces allowed massive monetary easing to support asset prices without boosting goods and services inflation. This is no longer true. In their book, “The Great Demographic Reversal,” authors Manoj Pradhan and Charles Goodhart make a compelling case on the demographics. As China’s population ages, it contributes more to demand than to supply, and therefore has an inflationary impact—the opposite of when a younger Chinese population entered the global market and boosted supply more than demand. Similarly, the energy transition and companies reducing their reliance on global supply chains tend to raise costs, and are therefore inflationary.

We are therefore likely to see a structural change in central banks’ attitudes, and markets have not come to terms with it yet. They will have to. In my view, we are facing a multi-year period where markets will relearn to price risk without such a strong central bank safety net. There will be a lot more volatility—we have gotten a taste of it already. The silver lining is that this adjustment brings new investment opportunities, particularly in fixed income, where the focus can finally shift squarely onto the analysis-driven search for value, rather than an obsessive hunt for yield at greater and greater risk.

- Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, data as of December 2022.

- Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York December 2022 Survey of Consumer Expectations. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.