The big shock announcement last week in global economic news was the downgrade in the US sovereign credit rating by Fitch.

But the real question we should be asking is does it matter?

After all, there was minimal impact from the decision by S&P to downgrade its US credit rating back in 2011. Apart from brief but sharp lift in risk aversion which saw equity markets sell off, US bonds were in even greater demand. Yields even trended downwards over the years following, helped by the quantitative easing policies of the US Federal Reserve at the time.

This time around, after Fitch’s downgrade, risk aversion has similarly increased as reflected in falling share markets, but the reaction by bond markets has been mixed.

Here is the US S&P500 index over the last 5 days:

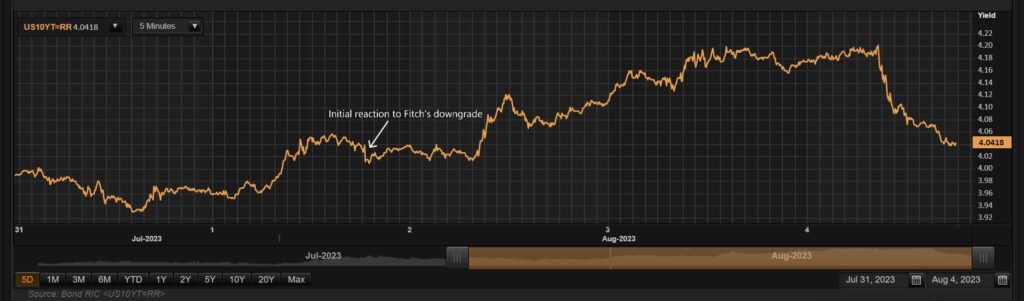

And here is the US 10 year benchmark yield:

You can see that there was an initial small sell-off in US bonds (yields fell) as risk aversion lifted. Yields on the 10-year government bond then rose to its highest in 10 months, but towards the end of the week, yields ended up close to where they were just before the downgrade.

After an initial knee-jerk reaction, financial markets, or bond investors, don’t seem to be particularly concerned about the downgrade.

But should investors be concerned?

The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that federal debt held by the public will reach 100% of GDP by 2024. That’s high – well above debt to GDP other triple-A sovereign ratings such as Germany’s at 47% of GDP and Australia’s, at 36% (according to the IMF).

Also read: De-anchoring From The Status Quo: What May Follow?

It also isn’t just the level of debt, it is also the trajectory of government finances. And federal government deficits are estimated to exceed well above 5% of GDP every year out to 2033. That means debt as a percentage of GDP is set to increase every year over the next ten years unless the budget, or the economy adjusts. That translates to an estimate of federal debt as a percentage of GDP of 119% of GDP by 2033.

Is that too high?

No one can really give a definitive answer to that question. Because there are also other considerations. Greece’s general government net debt reached around 130% of GDP when Greece’s bond market collapsed in 2009. On the other hand, government debt in Japan is around 160% of GDP, and no one bats an eyelid.

The structure of the economy matters too –Is the economy expected to continue to grow? Does that economy export more than they import? Is that economy a creditor to the world?

Unlike Japan, the US is a debtor nation, and has a large current account deficit. That means the economy spends more than it produces. Alternatively, that means that the rest of the world is financing spending in the US. In Japan’s case, the government may owe a large amount of debt, but the rest of the economy does not on a net basis. But in the US, both the government and the broader economy have a large liability. A net government debt of 160% of GDP in Japan would not be the same as 160% in the US.

Another possible signal of whether debt is sustainable or not, is whether interest rates are above or below the growth rate of the economy. The theory behind this logic is if interest rates are low, then it makes sense for the government to borrow to ‘invest’ in the economy, and then growth in the economy will service that debt.

If we apply this to the US, when interest rates were extremely low, especially in the last decade, it didn’t really matter that the government’s deficit was growing. In fact, it could even be seen as ideal because households were not spending in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

But today, with inflation higher, interest rates also higher and household spending being quite resilient, the same justification doesn’t apply.

That all being said, the level of debt which is deemed acceptable or not, is really up to investors. It is those who buy, hold or consider buying that debt who decides and when those investors become worried that the lender will default on their debt.

There is a natural confidence among investors when it comes to US treasuries and its key role in global financial markets. It is one the key benchmarks for setting all sorts of interest rates around the world for all debt securities. Moreover, US treasuries is still the ‘go to’ for the world to park funds in a ‘safe’ asset. It will take a while before the psyche of investors shift this perception of US treasuries as being the ‘safest’ in the world.

For countries with large FX reserves (ie. China, Japan) there is no other asset that can accommodate for the trillions of dollars worth of reserves that they hold. Even though some leaders of these economies hope for alternatives to investing in US treasuries, there isn’t an asset large enough. And while these economies continue to depend on exports as a driver of economic growth and support production and subsidize their domestic businesses, it will translate into needing to hold large amount of US dollar assets, and in particular, treasuries.

Like it or not, unless there are fundamental changes in how these major exporting nations structure their economies, they will continue to buy US dollars and therefore US treasuries.

In the meantime, that also limits any incentive for those in power in the US to address long-term budget sustainability.

While investors are not concerned today, part of the problem is that once investors decide that a particular form of debt is too risky, it is usually too late by then.